Fight or Flight Responses

Understanding hyperarousal and the nervous system

Have you ever noticed your heart pounding before a big presentation? Or perhaps you’ve felt your breath quicken when you heard a sudden loud noise? These reactions are examples of your body’s fight or flight response—a powerful and automatic response to perceived danger. While this system once helped our ancestors survive life-threatening events, in today’s world, it can sometimes work against us, especially when it becomes chronic or triggered by non-dangerous situations. This is known as hyperarousal, a state that can deeply affect mental well-being. In this article, we’ll explore what fight or flight means, how hyperarousal develops, and how you can regain control over your nervous system.

What is the fight or flight response?

The fight or flight response is your body’s natural reaction to threat or danger. It’s an instinctive, automatic process that prepares you to either confront or flee from a perceived threat. When the brain senses danger—real or imagined—it sends signals to the adrenal glands to release stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones lead to physical changes: your heart rate increases, your breathing quickens, your muscles tense, and your senses become sharper. Essentially, your body is gearing up for survival.

This response is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system and is deeply rooted in human evolution. In prehistoric times, it helped humans escape predators or defend themselves. Today, though the threats are less about lions and more about deadlines, arguments, or traumatic memories, the body often reacts the same way.

Understanding hyperarousal

Hyperarousal occurs when your fight or flight system becomes chronically activated, even when no real danger is present. This state is one of the hallmark symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and other trauma-related conditions. It means your nervous system is “on alert” more often than it needs to be.

People experiencing hyperarousal may feel jumpy, irritable, or constantly on edge. It’s as if the body is stuck in survival mode, scanning the environment for danger that isn’t really there. This heightened state of alertness can be exhausting and overwhelming, interfering with daily life and relationships.

Signs of a fight or flight response

When your body is in fight or flight mode, several physical, emotional, and behavioral signs may appear. Here are common examples:

Physical signs: Increased heart rate, sweating, rapid breathing, dry mouth, digestive issues, muscle tension, and shakiness.

Emotional signs: Irritability, panic, fear, anxiety, or anger without a clear trigger.

Behavioral signs: Avoidance of certain places or people, insomnia, hypervigilance (being constantly “on guard”), or startling easily.

For instance, someone who’s been in a car accident may tense up or feel their heart race when hearing screeching tires—even if they are safe. A person with anxiety may feel their chest tighten before a meeting, even if logically, there’s no danger.

The evolutionary role of the fight or flight responses

Biologically, the fight or flight response is governed by the amygdala—an almond-shaped structure in the brain that detects threats—and the hypothalamus, which activates the sympathetic nervous system. This results in a cascade of hormonal changes designed to help us survive.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this response was critical. For early humans, reacting quickly to danger could mean the difference between life and death. The fight or flight mechanism helped people avoid predators, survive natural disasters, and stay alert to environmental threats.

However, our modern environment has shifted. Today, we face psychological threats more often than physical ones—work stress, trauma reminders, or emotional pain—and our bodies react as if these are life-or-death situations. When this system is triggered too often or doesn’t shut off properly, it becomes maladaptive.

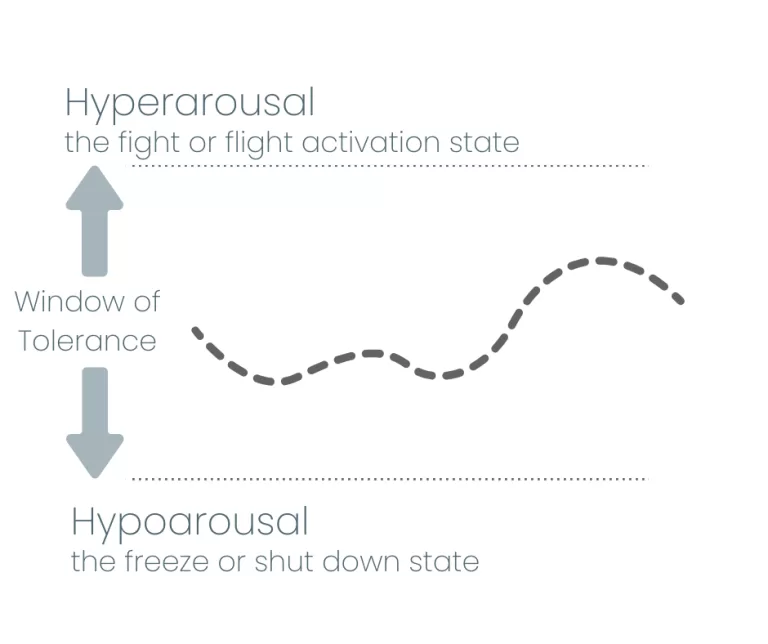

Nervous system responses and the window of tolerance

A helpful concept in trauma and nervous system regulation is the window of tolerance, first introduced by Dr. Dan Siegel. The window of tolerance represents the zone in which a person can function effectively and feel emotionally balanced. When we’re within this window, we can manage daily stressors, connect with others, and stay present—even during difficult situations.

However, when we’re pushed outside of this window—especially due to trauma, chronic stress, or emotional overwhelm—we tend to flip into one of two states: hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

Hyperarousal: the fight or flight state

As discussed earlier, hyperarousal is when the nervous system becomes highly activated. This is the classic “fight or flight” state where everything feels urgent or threatening. Signs include:

Racing thoughts

Panic or intense anxiety

Irritability or outbursts

Hypervigilance

Insomnia or restlessness

People in hyperarousal often feel like they can’t slow down. Their bodies are flooded with stress hormones, and they may feel unsafe even when there’s no actual danger present.

Hypoarousal: the freeze or shutdown state

On the other end of the spectrum is hypoarousal, sometimes called the “freeze” response. In this state, the nervous system shuts down in an effort to protect the body from overwhelming stress. Signs may include:

Emotional numbness or detachment

Depression or lack of motivation

Difficulty speaking or thinking clearly

Feeling disconnected from the body (dissociation)

Extreme fatigue or flat affect

People experiencing hypoarousal may feel stuck, invisible, or unable to act. It’s often associated with chronic trauma or a history of emotional neglect and is a survival strategy just like fight or flight—only it leans toward immobilization rather than activation.

Coping with hyperarousal and regulating the nervous system

The good news is that the nervous system can be regulated. Our bodies are capable of returning to a state of rest—known as the parasympathetic response—when we engage in practices that promote calm and safety. Here are some helpful techniques:

Breathwork – Slow, deep breathing (like box breathing or diaphragmatic breathing) can signal safety to the brain.

Grounding techniques – Using the five senses to connect with the present moment can help disrupt spirals of overactivation.

Mindfulness and meditation – These practices reduce stress hormone levels and promote nervous system balance.

Movement and exercise – Gentle physical activity like walking, stretching, or yoga helps discharge stress energy.

Sleep and nutrition – Prioritizing rest and nourishing foods supports brain and body recovery.

Safe social connection – Talking with a trusted friend or therapist provides emotional regulation and validation.

These methods help reset the nervous system and are foundational in addressing burnout and trauma-related stress.

Mental health counselling to address fight or flight responses

If you’re stuck in a loop of hyperarousal, therapy can provide a supportive path forward. Therapists trained in trauma-informed approaches help individuals recognize and reframe the patterns that keep their nervous system on high alert. Some beneficial therapeutic modalities include:

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): Helps identify and shift unhelpful thoughts that fuel fear and anxiety.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Encourages acceptance of uncomfortable sensations while pursuing meaningful life goals.

EMDR therapy: Particularly effective for trauma, EMDR helps reprocess distressing memories so they are no longer triggering.

Online therapy: Offers flexibility and accessibility for those unable to attend in-person sessions.

Counselling also supports the development of personalized coping strategies and offers a safe, non-judgmental space to process emotional experiences.

Final thoughts and resources

Living in a state of constant alert can leave you feeling exhausted, anxious, and disconnected from the present moment. While the fight or flight response once protected us, it’s not meant to run on overdrive. Understanding hyperarousal and its effects is the first step toward reclaiming calm and balance in your life.

Whether you’re dealing with past trauma, chronic stress, or ongoing anxiety, you don’t have to navigate it alone. Therapy can help you regain a sense of safety in your body and mind. If you’re ready to take the next step, consider reaching out to a therapist who can walk alongside you on your healing journey.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this post and across this website does not, and is not intended to, constitute medical, mental health, or therapeutic advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. This information does not create any therapeutic relationship and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. Consult with a licensed mental health provider for advice or support regarding diagnosis and treatment.

Get started with mental health therapy

Schedule your consultation today to see if we're a fit

Psychologist in Edmonton | Contact Us

Mendable Psychology | Edmonton Psychologists | Mental Health Counselling

Office located in Mayfield West Edmonton

- (587) 415-0850

- 10458 Mayfield Rd NW, Edmonton, AB

- [email protected]

- Schedule online

Read more from our blog

Mental Health Spiral

Navigating a Mental Health Spiral How to cope with a downward spiral, tolerate distress, and reduce overwhelm Spiraling mental health? In mental health discussions, you

5 Reasons To Choose A Local Therapist

5 Reasons to Choose a Local Therapist Benefits of working with a local mental health therapist Choosing a therapist? Here are 5 reasons to go

How Therapy Helps Mental Health

How Therapy Helps Mental Health Mental health counselling for prevention, support, coping, and treatment You may be wondering, “but how exactly does therapy help mental